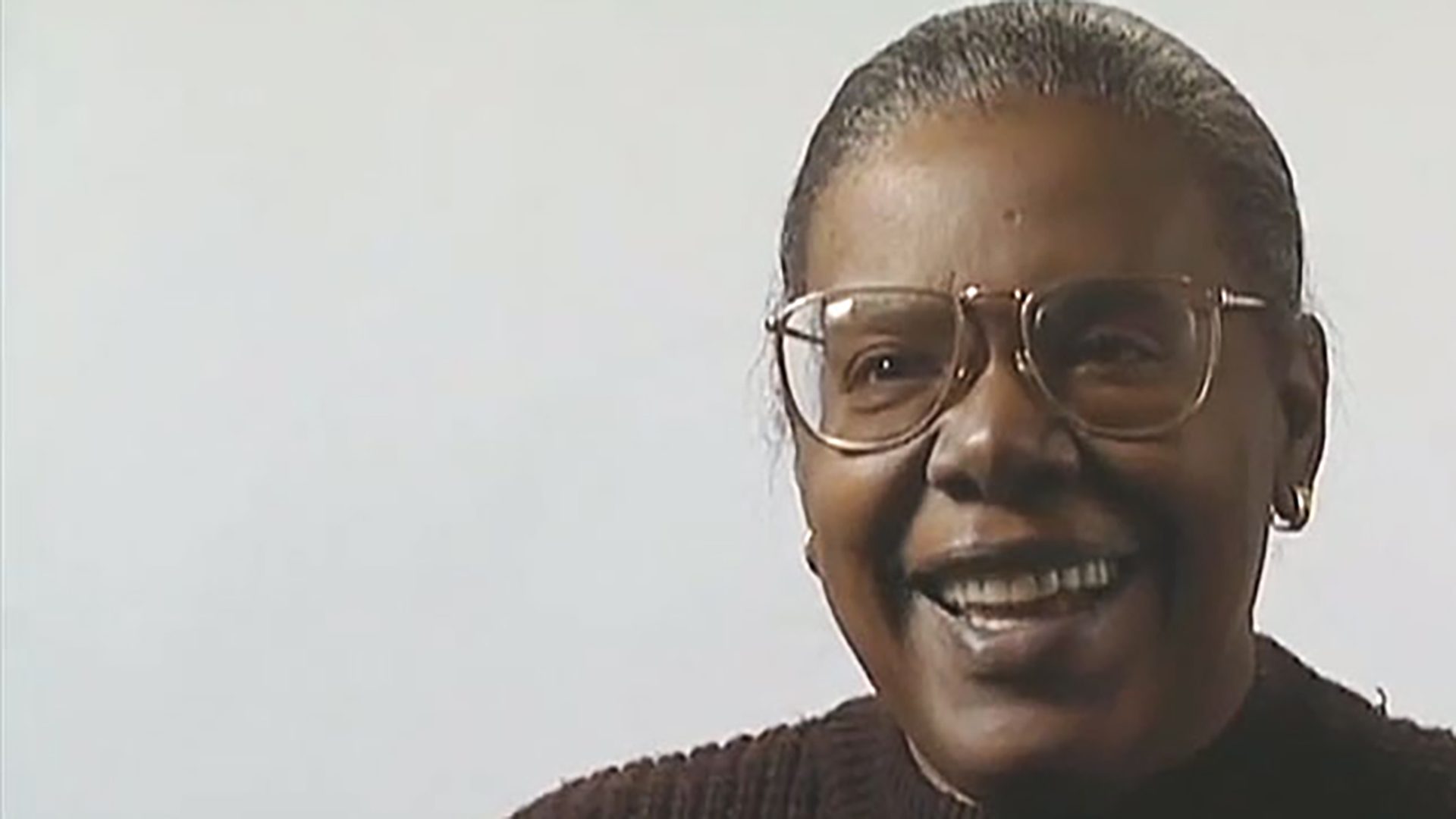

Survivor Interview – C.J. H.

C.J. is an osteosarcoma survivor. He talks about his leg amputation, returning to exercise using a prosthesis, and finding hope in his cancer experience.

I became an osteosarcoma survivor when I was diagnosed on December 23, 2002.

Sixteen months prior to my diagnosis, I started having a lot of pain in my rear heel bone. I went to a doctor and he said, “Well, you’re 17 years old, and you’re running 65 or 70 miles a week. You’re going to hurt in your heel.” “Okay, but it hurts pretty bad, and most people’s heels don’t hurt.” So I had an MRI done, and there was this really small growth that showed up. They were like, “Oh, don’t worry about it. Kids your age that play soccer or run have small growths all the time. It’ll probably go away. But there’s also a stress fracture, so no wonder you’re feeling pain. Take six weeks off from running.” I took the six weeks off and started running again, and there was no pain, but there was always this lump in the side of my heel.

The next year, I started running for UC-Irvine, and about midway through the season, my heel started hurting. I saw another doctor. He took a look at it, and he said the same thing. “You’re now running 80 miles a week and you at one point had a cyst. Of course, it’s going to hurt.” But in the back of my mind, I knew that something wasn’t right, so I went to a private doctor that wasn’t affiliated with the campus at UC-Irvine or the athletic department. He took one look at the x-ray and said, “Let’s get an MRI and we’ll see what’s going on.” What was a small growth, maybe half a centimeter or less sixteen months prior was, I think, four or five centimeters. It had grown quite significantly. He called me up about a week later and said, “I got the results, and I want you to go see this specialist. He’s really good when it comes to growths on bone.” I saw him on a late Friday afternoon. He had me scheduled Monday morning for a biopsy.

When I woke up from the surgery, the doctors sat down and informed me what was going on. Shortly thereafter, I started chemotherapy. I did that for several months. I did not handle it well. I did not like chemotherapy. I was angry. I was pissed. I didn’t have a good attitude with it. The worst feeling, to me, in the world is being nauseated, and I was always sick when I was on chemo. So I got through about three and a half months of chemo, and then the doctor said, “Okay, it’s time that we need to do the amputation.” The amputation was something that, originally, I had tricked myself into thinking that I was okay with. But I wasn’t always so positive during the next three and a half months. I think I was lucky to have those months, and that it wasn’t so immediate. I got to say, “I’m okay with it.” And I got to say, “No, I’m not okay with it.” I got to cry about it. I basically went through the acceptance process before it happened, which I think helped a lot. Because as soon as it did happen, I think my mindset changed a lot. So on April 28th, four months later, I had the surgery and was up walking the next day with crutches and everything.

I’ve had my leg amputated below the knee. I’ve adapted pretty quickly. The amputation was something that, to me, was just another physical challenge, just like running. I’d been through physical challenges. I’ve had injuries due to running. So that’s how I approached it. Immediately afterwards, I wanted to get out of bed. I wanted to start walking around, and I wanted to say, “Hey, look, I can do this.” There’s this popular notion that, “Oh, you’re an amputee. You can’t do certain things.” I was like, “No, I know you can, because I’ve seen other people that have done it. I’ve seen people that have run marathons, and I’ve seen people that have done Ironman competitions.” It’s not a disability. Anything that you want to do can be done. So I thought, “I’m going to prove that it can be done, not only to myself, but to everybody else that’s around to witness it.”

So after the amputation, when I woke up from the surgery, it was in a cast, and it had this really primitive prosthesis that looked like a mannequin’s foot. I was in the cast for three weeks and then there was a three-week period where I wasn’t using anything, because you had to wait for the limb to shrink down. Once I got the foot though, it took me about three days to start walking without crutches at all. From that point on, everything’s consistently gotten better. Once I finished chemo, there was a local non-profit organization that granted me a Fulfill-A-Dream. It’s for people that don’t fully qualify for Make-A-Wish. I didn’t qualify because I wasn’t under 18 at the age of my diagnosis. So they granted me the wish of a running prosthesis, which was a big help. I got that shortly after I finished chemo and started running on the prosthesis before I’d even re-grown hair. Between November 15th and April 2004, I set the national record in the 5K, and I was making leaps and bounds. I set personal records in the 5000 meters by two or three minutes at a time. I ran my first 5K in 25 minutes and then within six months ran it in 18 minutes.

I have regular chest CTs, because if osteosarcoma is going to go anywhere, it’s going to go to the lungs. The first CT that I had showed a spot on my right lung. I thought, “Great. It’s one thing after another.” I had another surgery to remove the tumor from my right lung on the 22nd of October, the day after my birthday. What fun. They actually found two spots, and they were both benign. They have no idea what caused them. Fortunately, I didn’t lose any lung capacity. Since then, I finally got to go a year without a surgery. I also do, as part of my follow-up therapy, Interferon treatment and Leukine treatment. I do the Interferon twice a week and the Leukine twice a week.

Body image was mostly related to the lack of hair. I liked my hair. It was gone, and I was sad. I didn’t feel comfortable dressing certain ways. I usually tried to look like a slob, because that’s how I felt. As far as losing weight, I didn’t really notice at first. I went from 140 pounds to 110. I think at a few times I was below 110. I felt fatigued, so I’m sure that when I walked around that I was presenting this lowly, sickly look to everybody. To me, the leg is like hardware. Guys and girls walk around with their bikes. They’re like, “Hey, look at my bike. It’s cool. It’s hardware.” So I approached it the same way. That was a true reaction – that wasn’t a defense mechanism on my part. I thought it was cool. I liked wearing shorts. For a long time, it helped that it was summer. But even once it started to get cold, I wasn’t happy the first winter, because I was wearing pants all the time. I was like, “Wait. I want to show this off.”

I think lots of things gave me hope. When I first met my doctors, I had full faith in them. I wanted to ask a lot of questions. Everybody talked about bedside manner, but when I first sat down and talked to my doctor, he made me feel like there weren’t even other people in the room, because it was just us. I think that, from the start, gave me a lot of hope. When I went in to have chemo and I didn’t want to, I was like, “I trust this guy. I don’t think that he’s going to do anything wrong.” He was progressive. He was looking into new therapies and doing clinical trials. Seeing all the people around me that had survived cancer also gave me hope. The first thing that my parents did was rush out and buy It’s Not About the Bike. I sat there on Christmas night and read it, and then I sat there two days later and read it again. That, of course, gives you hope. It seems like everybody knows somebody that’s either died from or survived cancer. I looked at the people that had survived cancer.

Survivorship, to me, is luck. It’s proof that anything’s possible. It’s proof that if you put your mind to something, anything’s possible. And that’s not just me putting my mind to something, but that’s people in general putting their mind to something. If I was born 50 years earlier, and I was diagnosed with cancer, I probably wouldn’t be having this conversation with you today. But survivorship truly is the proof that if people as a whole put their mind to anything, it’s possible. Nobody survived cancer 100 years ago. But today, there are ten million people that survive cancer in the United States.

Livestrong means trying to be a positive influence on other people’s lives. To me, it’s fulfilling an obligation. I’ve had something that many people would describe as terrible, but it’s also given me the opportunity to make an impact in other people’s lives. Every time that I’m running and somebody sees me, they’re like, “You’re a major influence,” or “You inspire me.” That’s what I want to do. I think if you can inspire somebody else, then you’re probably doing something right, and you probably are fulfilling what a lot of people would describe as living strong.

My name is C.J. Howard. I’m 21 years old, and I’m an osteosarcoma survivor.