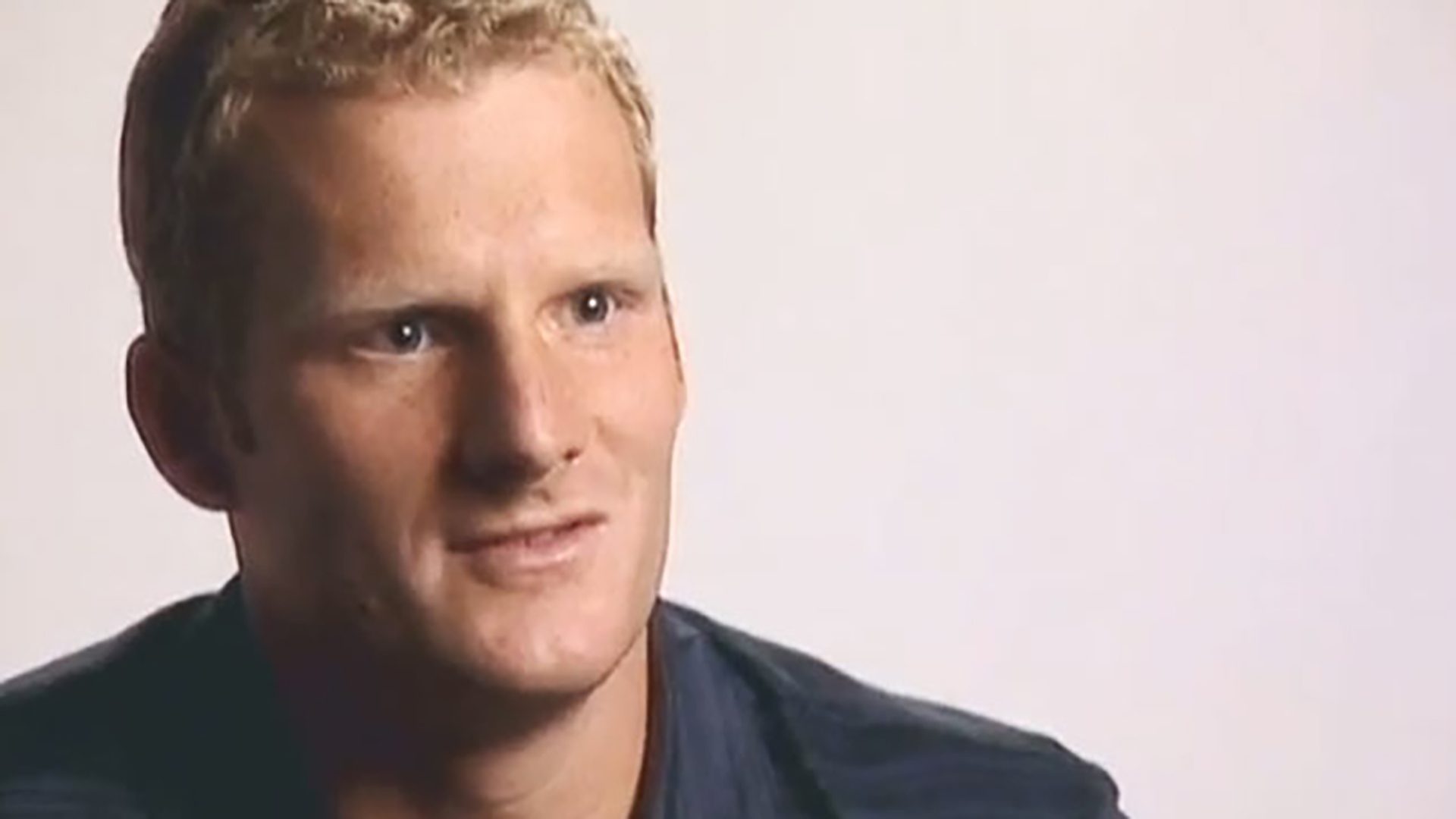

Survivor Interview – Tim M.

Tim is a testicular cancer survivor. He discusses losing his mother to lung cancer, dealing with survivor guilt, and out-of-pocket expenses.

I became a survivor in November of 1999 when I was diagnosed with testicular cancer.

I had an orchiectomy a couple of days after diagnosis. My tumor was part seminoma, part non seminoma, and there was a discrepancy. I decided at the time, being 25 years old, that I wanted to be aggressive with it, so I was fired up to get a lymph node dissection done. There was that ten percent chance that I would lose my ejaculatory function. As it turns out, that did happen to me, so that’s one of the things that I now have going forward. About a year later, there were enlarged lymph nodes in my abdomen, so over a course of three weeks, they decided that they wanted to go in and biopsy that. It turned out to be negative, which is good.

Everything seemed to be pretty good with regard to my scans, my checkups, and my blood work until last November. I went in for a CAT scan. The doctor said, “The abdomen looks fine, but there’s a bunch of stuff in your chest that we’re concerned about. I want to get a PET scan to try and get a better idea of what we’re dealing with.” My chest lit up like a Christmas tree in the PET scan. He was fairly certain that it had come back. They did a biopsy of some lymph nodes in between my lungs. When they removed those, it turned out to be sarcoid. It was all benign, no cancer. Obviously, a relief.

The retrograde ejaculation will probably be there for the rest of my life. I did bank sperm before any of my treatment. That was an interesting experience in and of itself, going to Brigham Women, going into this hospital room and the nurse gives you the cup, and you go in and do it. It was actually funny, because I was going to donate sperm, and my mother turns to me and goes, “Sweeties, I’ll drive you over there.” I was like, “No, no, no, no. Listen, Mom, I’m taking the T.” The last thing I could think of was getting out of the car, giving my mom a kiss, and going to do what I had to be doing. I said, “I’ll take the T, Mom. I need to deal before I get there.” It was a comedy in and of itself.

My mother was diagnosed with lung cancer after I was diagnosed. She started to get headaches and her speech would start to get slurred, almost like her tongue was too big. She went to the doctor, and they thought it might be her thyroid, so they did an x-ray of her neck and the top of her lung. They saw this big tumor, so they went in and she had a bunch of CAT scans. About five days later, they did an MRI of her brain, and they said, “We need to keep you here now, because you’ve got four tumors in your brain and one of them is butting up against your brain stem. If we didn’t catch this, you probably would have died within a week.” She went and had emergency brain surgery. From the get-go, she was really having a tough start. I moved to Boston about two years ago to be closer to her and help out. She passed away a year-and-a-half ago from the lung cancer.

I had a very difficult time when my mother was diagnosed, and she was going through her chemo. For a long time, probably for the two years that she was going through it, I wanted my cancer to come back. When I went to the doctor, part of me, in a weird way, wanted that cancer to come back, because I felt I had gotten off too easy. I wanted to go through chemo with her as she was getting her body destroyed. It may have been a little different if I hadn’t watched my mother a year after I had been diagnosed. It definitely took me a long time to deal with that guilt. To be honest, it was that scare in November of this past year that really made me think, “All right, now I’m gonna have to deal with what I’m gonna have to deal with, meaning chemo.” Now there’s a definite possibility I’m gonna have to do it. It’s put up or shut up. It took that real scare to make me realize, “Suck it up. Don’t feel sorry for yourself, and move on.”

Everybody talks about survivor’s guilt. I definitely had survivor’s guilt. It took me a while to say, “All right. I dodged that bullet.” It’s okay that I dodged that bullet, and when I went to get a CAT scan, I didn’t have to hope that something would turn up so that I would have to go through more treatment. I became very comfortable in hospitals. I like hospitals, because in hospitals I felt that I was being taken care of. I didn’t mind getting stuck with needles, because it was a weird kind of safe haven for me. This past December, when I saw this doctor at Dana-Farber, he said, “We’re just gonna see you once a year now,” and that was coming from when I was seeing a doctor every four months. I said, “Wait. Why?” And he goes, “Because you’re fine. You’re all right.” But it takes a while to be like, “I guess I am okay.” It’s a very difficult and weird feeling.

I’ve battled depression for the past four years, in no small part to my mother and her death and illness. There’s also some heredity. I think I may have been more predisposed than some. It’s in my family. I’ve seen a counselor. I’ve seen a psychiatrist. I’m on medication. I see a psychologist. When my mother was going through her cancer, there was a really neat guy who was head of the psychiatry unit. He retired two years ago from his post. When he retired, the only patients that he would take on were terminally ill patients. So my mother went to see him. We would go in as a family and talk. She wanted to be at peace with each of her kids and her husband before she died.

I don’t think I ever got angry. There were two things that I always felt angry about, with regard to my mom dying. She wouldn’t ever see me get married and she would never see my kids, her grandkids. We would have a lot of conversations about death and about her dealing with being able to be at peace with people. Even though she would get angry and say, “This really sucks,” she would say, “I’ve seen four of my kids grow up, be happy and be successful. I’ve seen two of them get married. I’ve seen four grandchildren be born.” For her, she really was saying, “I count my blessings.”

My out-of-pocket expenses for the past four years were probably three grand a year, roughly. The first couple of years, I ignored all of these insurance things, because I had too much on my mind with regard to what I was dealing with. That came back to bite me in the ass, because then it goes to the creditors and your credit gets screwed up. My insurance in New York was pretty good, but my insurance at my last job was not good. For every PET scan or CAT scan that I had done, they only paid 90% of it, so I had to pay the extra 10%. That’s in addition to meeting my deductible and out-of-pocket expenses. When I resigned, I got COBRA insurance, which I can have for up to 18 months. That’s always been a very difficult thing. It’s a pain. At 25 years old, you don’t really know how to deal with it.

Survivorship. I think it means dealing with issues beyond your cancer. For me, that would be retrograde ejaculation. For me, that would be dealing with the guilt of not getting off easy. For me, it would be keeping awareness up and having that sensitivity of having had cancer and also having seen a mother die of a terminal cancer. To me, survivorship in that sense means it gives you a much deeper appreciation for things. It makes you a much better person. It adds an element to your personality and sensitivity to your personality that I think a lot of people that have never had to deal with cancer themselves aren’t able to have.

My name is Tim Madden. I’m 29 years old, and I’m a five-year testicular cancer survivor.