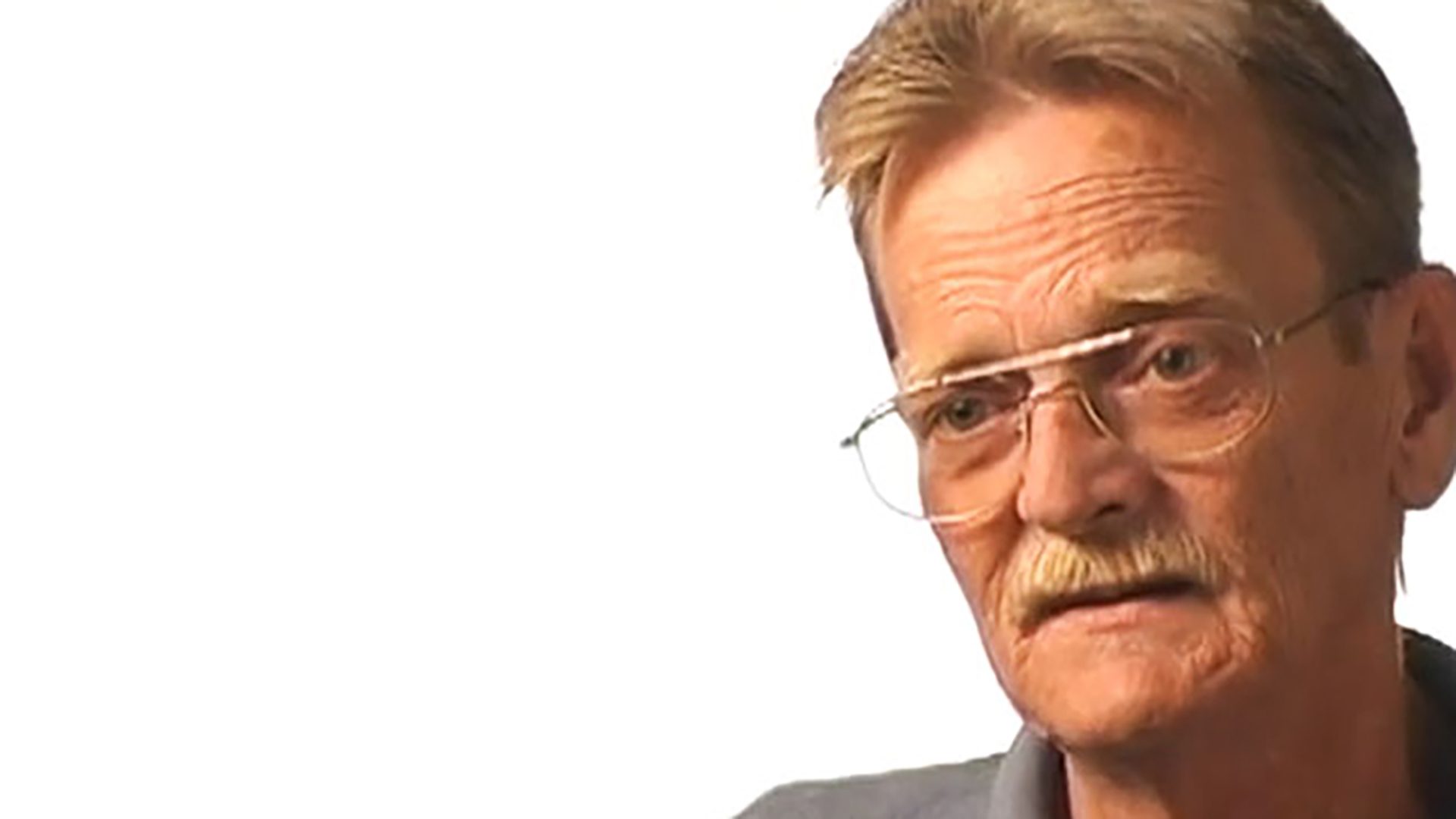

Survivor Interview – David D.

David is a pancreatic cancer survivor. He talks about experiencing aftereffects of treatment, living with uncertainty, and planning his medical future.

In February of 1999, they diagnosed me with pancreatic cancer. Prior to that, I had had digestive problems, which they attributed to gallstones irritating the pancreas. They had planned on going in and doing an exploratory surgery and a possible Whipple. What should have been a seven to eight hour surgery turned into about an hour and a half. They closed me up, came out and told my wife, “He’s got pancreatic cancer. The largest tumor is right at the head of the pancreas, where we cannot remove it, because all the blood vessels come in together. The only thing we could do was sew him back up.”

When my wife found out, the doctor said, “Do you want me to tell him or do you want to tell him?” She says, “I’ll tell him.” She came in the next morning, and she told me, “The bad news is, you’ve got pancreatic cancer. They gave you six months to a year to live. The good news is, you better hurry up and get out of here, you got trash at home to take out.”

From there, we started the treatments and started changing my life. In March, I started a chemotherapy called Gemzar and 5FU. Almost at the same time, I started six weeks of radiation therapy, five days a week. I told my wife at one point, “I’ve come to the decision. What am I going to do to control it and not let it control me?” It being the pancreatic cancer. I still wanted to live. I figured I fought long enough to get to the top of the hill, and if I’m gonna go downhill, I’m gonna be the one to put the brakes on when I feel like it.

Attitude makes a big, big difference. It was hard to do, but we found good in it. You could either look at the bad part of it or you could pick out the good things. I chose the good. I’d tell people, “Don’t feel sorry for me. I may have cancer, but my cholesterol is 180.”

Attitude makes a big difference, even for the caregivers. Aggravate the patient. Ask them all the time, “Are you hungry? What do you want to eat?” If they say, “Quit aggravating me or I’ll strangle you,” say, “No, you don’t have the strength.” Make them mad every now and then. There were times I didn’t want to get out of bed. My wife would come in the bedroom and say, “Honey, if you’ll sit up for five minutes, then you can lay down for an hour.” Compromise. Find something in between. Sometimes I feel like it’s a little tougher for the caregivers as it is for the patient.

I have what some people know as chemo brain. It jumbles your thoughts. You slur your words. Other than that, there are no long-term effects from the chemo. The radiation therapy caused me to have a GJ jejunostomy. To me, it’s the same thing as a gastric bypass. They go in and cut out scar tissue in my stomach from the radiation therapy. I was supposed to be in the hospital for a week. I got out February 17, 2002. The first surgery didn’t take. They had to do a second one. They ended up taking out three-quarters of my stomach. I ended up with two staph infections, blood clots on my lungs, and infections in both my central ports. But I made it.

Originally, when they planned on doing the Whipple procedure, they had warned me that they could take out 80% of my pancreas and I still would not be diabetic. If they took out anymore, I would be diabetic. You can actually live with 100% of your pancreas gone, but it does make you diabetic. Luckily, my blood sugar counts never got to that point. I was glad and very lucky.

Before all this started, I weighed 210 pounds. I now weigh 138 on a good day. I used to be a sweets lover. Now, five minutes after I eat something sweet, I’ll start cramping up. I get tired easy. I bruise easily. I cut myself very easily now.

Now I have to have five to six small meals a day, minimum. With three-quarters of your stomach gone, whatever you eat is almost through your system within three to four hours. It changes eating habits and bowel movements. It changes your bodily feeling, because when I cramp, I hurt. At one point, I had to have a pain block done just because of the cramping and the hurting. Pain blocks are great. They last anywhere between six months to a year, and they do help.

I’m 50 years old now. I was 45 when I was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. I was 44—almost a year to the day before I was diagnosed with pancreatic—when they diagnosed me with lung cancer. They took out half my lung, a mass off my left breast, and half of one rib; which, by the way, ribs do grow back. I didn’t know that.

I can’t say if the pancreatic caused the lung cancer. They say lung cancer cannot cause pancreatic, but pancreatic can cause lung. At the same time, I was a smoker. So that’s still a toss-up. The first go-around with lung cancer, I figured, that’s over and done. I won that war. I didn’t realize that was just the first of many battles to come.

When I first found out, I started writing a journal, putting down different thoughts that I had, because it would make me feel better. Some of them were good thoughts, some of them were bad thoughts, but they had to be written down, because it was part of what I considered therapy: that attitude. I kept not really focused on it, because if you focus on it, it’s gonna take over. You can make it as large or as small as you want to. But it’s always there. Even five years later, it’s still in the back of my mind. Am I gonna make it from here on out? I’ll fight the battle again. I know how to do it. I’ll do it again.

I cannot work. I feel at times that I could work, and at times I wish I were back at work, but no. Social Security sent me one of those ‘go back to work’ cards, almost like a ‘get out of jail free’ card in Monopoly. “Take this card into any employer. They’re guaranteed to hire you, and we guarantee it won’t cut into your Medicare.” But there are still days now where I can barely get out of bed, because I hurt. It’s from the aftereffects of the cancer, the surgeries, and the radiation therapy. Then there are other days I get up and can’t anybody keep up with me. I find different things to fill my time. I do yard work here and there. I write. I build little projects, help people out. So I work, but not what most people call work.

My surgeon, at the time, told us, “I would suggest that if you have any life insurance, retirement, 401-Ks, what-have-you, cash them in, have a good time, because you’ve got six months to a year to live. Enjoy it while you can.” We did that. Here it is, five years later. I’m broke, but I’m alive.

Even if I hadn’t done what the doctor told me, five years later, it still would have been gone to pay medical bills. But there again, that’s just another battle you have to overcome. It’s hard to adjust, but it can be done, because you’re thankful every day that you’re still alive. Money can improve your health, but it can’t buy you permanent health or happiness.

I’m donating my body to science, because I feel like anything they can find out about pancreatic cancer, the better off people will be. Looking for the good in it, I always told everybody, “I figured out how my wife can make money on it.” I tell them, “Social Security pays $255 in death benefits. The University of Kentucky will have to drive to Paducah to pick my body up. They charge $225. She’s made 30 bucks.”

I’ve got a cousin that says, “No, she can make the whole $255. We’ll throw you in the back of the SUV, ice you down with some beer around you, and take you up there. Cop stops us on the way, we’ll pick you up, put you behind the steering wheel, put a cigarette in one ear, can of beer in the other, put sunglasses on you, and when the cop comes up, say, ‘Look, Officer, you scared him to death.’” People look at me and think, “That’s sick.” And I say, “To me, it’s a positive outlook.”

Survivorship means being able to say I came close to, not necessarily dying, but being maimed, hurt, and I survived it. The odds were against me, but I turned them around in my favor. That sums it up for me right there. If it wasn’t for that word survivorship and me wanting to get to that point, then those odds a long time ago would have taken over, and I wouldn’t be able to say today what survivorship means to me.

I am David Driver, and I am a two-time cancer survivor.